Bangkok’s lavish, air-conditioned malls consume as much power as entire provinces

by Adam Pasick

Selfie city. (Reuters/Athit Perawongmetha)

How much luxury retail does one city need? Bangkok seems determined to find out. The Thai capital’s newest high-end mall, EmQuartier, opened March 27 featuring brands including Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Dior, Prada, Cartier, Dolce & Gabbana, Tiffany, Fendi, and Balenciaga.

EmQuartier opposite Emporium Mall opened recently and it’s packed! pic.twitter.com/BdMmsNhVCQ

— Willy Thuan (@willythuan) April 2, 2015

It joins more than half a dozen similar shopping meccas within a three-mile (5 km) stretch along the city’s central Sukhumvit Road, many of them boasting the same expensive brands.

EmQuartier Mall in Bangkok.

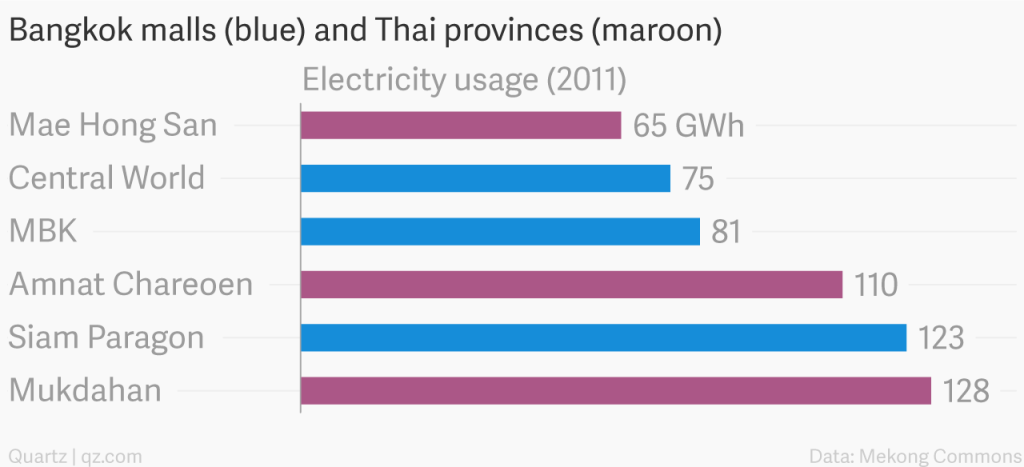

But the true cost may extend beyond Thailand’s borders. In part because of the city’s intense climate—it is one of the hottest big cities in the world—Bangkok malls and their massive air conditioning systems consume immense amounts of electricity. The huge Siam Paragon mall consumes nearly twice as much power annually as all of Thailand’s underdeveloped Mae Hong Son province, home to about 250,000 people.

As Thailand’s natural gas supplies run low, that electricity increasingly comes from environmentally destructive dams on the Lower Mekong River, particularly in Laos. Some 240 million people in the region depend on the river for their livelihoods.

EmQuartier is owned by the descriptively named Mall Group, Thailand’s second-biggest retailer, which is slugging it out with its larger rival Central Group, owner of several mega-malls along the Sukhumvit strip. Along with a few smaller rivals, the companies are plowing huge sums into building even more. The Mall Group is spending 30 billion baht ($929 million) on EmQuartier and two adjacent projects, the revamped Emporium mall, and the yet-to-be-built EmSphere complex.

Part of the appeal of Bangkok malls has to do with the city’s climate—for much of the year, it is simply too hot to be outdoors. The aggressively air-conditioned malls have become the de facto place for people to congregate, eat at the malls’ often excellent food courts, and take innumerable selfies.

But an even larger factor is Thailand’s rapidly growing middle class, which has newly disposable income to spend. “Their interest in the materialism trend gave a big support to luxury goods in many categories,” Euromonitor noted in a recent report on the Thai retail sector. And the country is also, crucially, home to a small but extremely wealthy elite. So-called “Hiso” (for High Society) Thais are major luxury spenders, accounting for the presence of the city’s Lamborghini and Ferrari dealerships and five stand-alone Prada outlets, including a huge new store at EmQuartier.

Foreign tourists, especially from China, are another important element in the mix, although arrivals have taken a hit in the wake of last year’s military coup. Import duties often mean prices are significantly higher than in rival destinations like Hong Kong and Singapore. Despite those setbacks, prime-grade mall vacancy rates are low (pdf), according to analysts at JLL Thailand, even as the amount of supply edges higher:

Still, not every project is a success. The Central Embassy mall opened in 2014 on the grounds of the former British Embassy, with premium tenants, and an eye-catching design. But the mall had the misfortune to open just 10 days before the coup. Crowds have been notably sparse, prompting some in Bangkok to dub it “Central Empty.”

[H/T Quartz]

For bizarre stuff and news oddities check out the link: